The oropharyngeal airway (OPA) is a vital tool in emergency and surgical settings, designed to maintain a clear airway by preventing the tongue from obstructing the throat. This article explores the uses, insertion techniques, and care of the OPA, highlighting its role in effective airway management and patient safety.

Understanding the Oropharyngeal Airway

Definition and Purpose

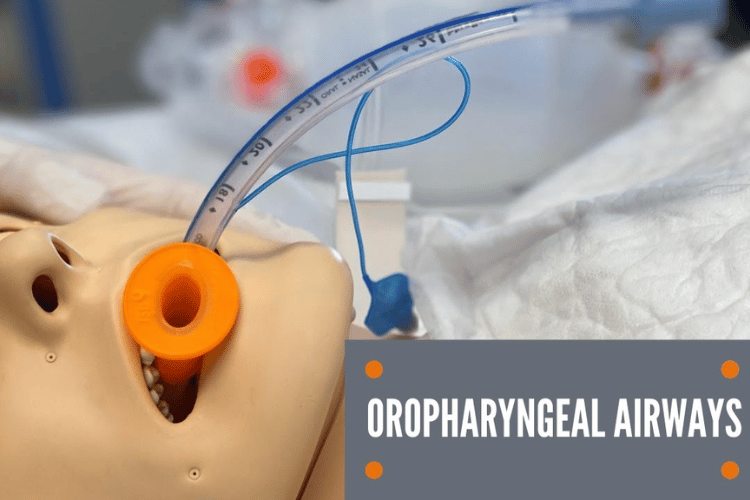

The oropharyngeal airway (OPA) is a medical device designed to maintain or open a patient’s airway by preventing the tongue from obstructing the oropharynx, the area at the back of the throat. This device is commonly used in emergency and surgical settings to ensure proper airflow to the lungs, particularly in unconscious patients who are unable to maintain their own airway. By keeping the tongue from collapsing backward, the OPA facilitates unobstructed breathing and allows for effective ventilation, whether through spontaneous breathing or assisted methods like bag-valve-mask ventilation. The OPA is typically used in patients who are unresponsive and lack a gag reflex, as the presence of a gag reflex could lead to complications such as vomiting or aspiration. It is a simple yet essential tool in airway management, often serving as a first-line intervention in cases of respiratory distress, cardiac arrest, or during anesthesia. Proper sizing and placement of the device are critical to its effectiveness, as an incorrectly sized OPA can either fail to maintain the airway or cause trauma to the oral cavity.

Types of Airway Devices

Airway management involves a variety of devices, each tailored to specific clinical scenarios. The oropharyngeal airway is one of several tools used to ensure adequate ventilation and oxygenation. Below are the primary types of airway devices and their unique features:- Oropharyngeal Airway (OPA):

- Designed to prevent the tongue from obstructing the airway in unconscious patients.

- Available in various sizes to accommodate different age groups, from infants to adults.

- Typically made of rigid plastic with a curved shape that conforms to the anatomy of the mouth and throat.

- Nasopharyngeal Airway (NPA):

- Inserted through the nostril to bypass obstructions in the nasal passage or oropharynx.

- Suitable for patients with an intact gag reflex or those who cannot tolerate an OPA.

- Made of soft, flexible material to minimize discomfort during insertion.

- Endotracheal Tube (ETT):

- A definitive airway device inserted into the trachea to provide a secure and controlled airway.

- Used in patients requiring mechanical ventilation or during surgical procedures under general anesthesia.

- Requires advanced training for proper placement and is often guided by laryngoscopy.

- Supraglottic Airway Devices:

- Includes devices like the laryngeal mask airway (LMA), which sits above the vocal cords to facilitate ventilation.

- Ideal for short-term use or as a bridge to more advanced airway management.

- Tracheostomy Tubes:

- Surgically placed directly into the trachea through the neck for long-term airway management.

- Commonly used in patients with chronic respiratory conditions or those requiring prolonged mechanical ventilation.

Arthur Guedel and His Contributions

Arthur Guedel, an American anesthesiologist, made significant contributions to the field of airway management and anesthesia. He is best known for developing the modern oropharyngeal airway, often referred to as the Guedel airway, which remains widely used in clinical practice today. Guedel’s design improved upon earlier airway devices by incorporating a rigid, curved structure that effectively prevents the tongue from obstructing the airway while minimizing the risk of injury to the oral cavity. In addition to his work on the OPA, Guedel developed the "Guedel classification of anesthesia stages," which describes the depth of anesthesia in four stages: induction, excitement, surgical anesthesia, and overdose. This classification system provided a framework for monitoring patients during anesthesia and remains a foundational concept in anesthesiology. Guedel’s innovations revolutionized airway management and anesthesia, making procedures safer and more effective for patients. His contributions continue to influence modern medical practice, underscoring the importance of his work in advancing patient care.Indications for Use

The oropharyngeal airway (OPA) is a critical tool in airway management, primarily used in patients who are unresponsive and unable to maintain their own airway. Its primary indication is to prevent the tongue from obstructing the oropharynx, which can compromise airflow to the lungs. The device is most effective in individuals who lack a gag reflex, as the presence of this reflex can lead to complications such as vomiting or aspiration. Common scenarios for OPA use include cardiac arrest, respiratory failure, and during anesthesia to maintain a patent airway. Additionally, the OPA is often employed in emergency settings where rapid airway management is required, such as trauma cases or overdose situations. It is also used as a temporary measure before more advanced airway devices, like endotracheal tubes, are placed. Proper sizing and placement of the OPA are essential to ensure its effectiveness and to minimize the risk of injury to the oral cavity or pharynx.Management of the Airway in Semiconscious Patients

Managing the airway in semiconscious patients presents unique challenges, as these individuals may have a partially intact gag reflex and varying levels of airway obstruction. The use of an oropharyngeal airway in such cases requires careful assessment to avoid triggering complications. For semiconscious patients, the nasopharyngeal airway (NPA) is often preferred, as it is better tolerated and less likely to provoke a gag reflex. However, in situations where the OPA is deemed necessary, it is crucial to monitor the patient closely for signs of discomfort or adverse reactions. The device should only be used if the benefits of maintaining a clear airway outweigh the risks of potential complications. In some cases, sedation or anesthesia may be required to facilitate the use of an OPA in semiconscious patients. Proper training and experience are essential for healthcare providers to manage these scenarios effectively and ensure patient safety.Airway Obstruction Scenarios

Airway obstruction can occur in various clinical situations, ranging from trauma to medical emergencies. The oropharyngeal airway is particularly useful in addressing obstructions caused by the tongue, which is a common issue in unconscious or unresponsive patients. Below are some common scenarios where the OPA is indicated:- Cardiac Arrest: During cardiac arrest, the loss of muscle tone can cause the tongue to fall back and block the airway. The OPA helps maintain patency, allowing for effective ventilation during resuscitation efforts.

- Overdose or Intoxication: Patients who are unconscious due to drug or alcohol overdose often experience airway obstruction due to relaxation of the tongue and surrounding muscles. The OPA provides a simple and effective solution in these cases.

- Post-Seizure Care: After a seizure, patients may have reduced consciousness and an obstructed airway. The OPA can be used to ensure adequate airflow while monitoring for recovery.

- Trauma: In trauma cases, particularly those involving head or neck injuries, the OPA can be used to secure the airway temporarily while avoiding more invasive procedures.

Comparison with Nasopharyngeal Airways

The oropharyngeal airway and the nasopharyngeal airway (NPA) are both essential devices in airway management, but they differ in their indications, design, and application. Understanding these differences helps healthcare providers choose the most appropriate device for each clinical situation.- Tolerance and Patient Comfort:

- The OPA is suitable for patients who are completely unresponsive and lack a gag reflex, as it can provoke vomiting or discomfort in those with partial consciousness.

- The NPA, made of soft, flexible material, is better tolerated in semiconscious patients or those with an intact gag reflex, as it bypasses the oral cavity and is inserted through the nostril.

- Indications:

- The OPA is primarily used in cases of tongue-related airway obstruction, such as during cardiac arrest or anesthesia.

- The NPA is preferred in patients with facial trauma, trismus (jaw clenching), or when oral access is limited.

- Ease of Use:

- The OPA is relatively simple to insert but requires proper sizing to avoid complications.

- The NPA is slightly more complex to place but is less likely to cause trauma if inserted correctly.

- Complications:

- The OPA can cause oral trauma or trigger a gag reflex if used inappropriately.

- The NPA may lead to nasal bleeding or discomfort, particularly in patients with nasal abnormalities or clotting disorders.

Insertion Techniques

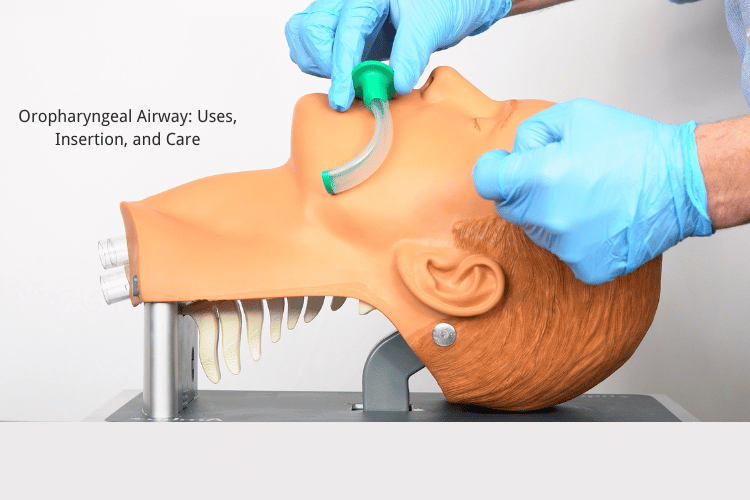

Step-by-Step Insertion of the Oropharyngeal Device

Proper insertion of the oropharyngeal airway (OPA) is essential to ensure its effectiveness and to minimize the risk of complications. The following step-by-step guide outlines the correct technique for placing an OPA:- Assess the Patient: Confirm that the patient is unresponsive and lacks a gag reflex, as the presence of a gag reflex can lead to complications such as vomiting or aspiration. Ensure the airway is clear of any visible obstructions, such as blood, vomit, or foreign objects.

- Select the Correct Size: Choosing the appropriate size is critical for the device to function effectively. Measure the OPA by holding it against the side of the patient’s face. The correct size should extend from the corner of the mouth to the angle of the jaw.

- Position the Patient: Place the patient in a supine position with the head tilted slightly back to open the airway. Use the head-tilt, chin-lift maneuver unless a cervical spine injury is suspected, in which case a jaw-thrust maneuver should be used.

- Insert the Device:

- Hold the OPA with the curved end pointing upward (toward the roof of the mouth).

- Gently open the patient’s mouth using a tongue depressor or by grasping the jaw.

- Insert the OPA into the mouth, sliding it along the roof of the mouth.

- Once the device reaches the back of the throat, rotate it 180 degrees so the curved end points downward, following the natural contour of the tongue and oropharynx.

- Ensure Proper Placement: The flange of the OPA should rest against the patient’s lips, and the device should not cause any visible trauma. Check for effective airflow by observing chest rise and listening for breath sounds.

- Secure the Device: If necessary, secure the OPA in place using tape or other stabilizing methods to prevent displacement during ventilation or patient movement.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

Improper insertion of the oropharyngeal airway can lead to complications or reduced effectiveness. Here are some common mistakes to avoid:- Using the Wrong Size: An OPA that is too small may fail to keep the airway open, while one that is too large can cause trauma to the oral cavity or pharynx. Always measure the device before insertion.

- Forcing the Device: Forcing the OPA into the mouth can cause injury to the teeth, gums, or soft tissues. Use gentle, controlled movements during insertion.

- Neglecting to Rotate the Device: Failing to rotate the OPA during insertion can result in improper placement, with the tongue remaining obstructive. Ensure the device is rotated 180 degrees once it reaches the back of the throat.

- Ignoring the Gag Reflex: Attempting to insert an OPA in a patient with an intact gag reflex can lead to vomiting and aspiration. Always assess the patient’s level of consciousness and reflexes before proceeding.

- Improper Patient Positioning: Inadequate head positioning can make insertion more difficult and reduce the effectiveness of the device. Ensure the airway is properly aligned before attempting placement.

Tips for Successful Intubation

While the oropharyngeal airway is not an intubation device, its proper use can facilitate successful ventilation and serve as a bridge to more advanced airway management techniques, such as endotracheal intubation. Here are some tips to ensure success during airway management:- Prepare All Equipment: Before beginning, ensure all necessary equipment is readily available, including suction devices, bag-valve masks, and advanced airway tools like endotracheal tubes or laryngoscopes.

- Practice Proper Airway Alignment: Use the head-tilt, chin-lift maneuver or jaw-thrust technique to align the airway for optimal airflow. Proper alignment reduces the risk of complications during both OPA placement and intubation.

- Use Suction When Needed: Clear the airway of any secretions, blood, or vomit using a suction device before inserting the OPA or attempting intubation. A clear airway improves visibility and reduces the risk of aspiration.

- Monitor the Patient Continuously: Observe the patient for signs of effective ventilation, such as chest rise and fall, and listen for breath sounds. If ventilation is inadequate, reassess the airway and adjust the device as needed.

- Communicate with the Team: In emergency settings, effective communication with the healthcare team is essential. Assign roles and ensure everyone is aware of the plan for airway management.

- Practice Regularly: Airway management skills require regular practice to maintain proficiency. Simulated training scenarios can help healthcare providers refine their techniques and build confidence.

Care and Maintenance of Airway Devices

Cleaning and Sterilization Procedures

Proper cleaning and sterilization of airway devices, such as oropharyngeal airways (OPAs), are essential to prevent infections and ensure the devices remain safe for use. After each use, the device must be thoroughly cleaned to remove any biological material, such as blood, mucus, or saliva, which can harbor harmful pathogens. The cleaning process typically begins with rinsing the device under running water to remove visible debris. A soft brush can be used to scrub hard-to-reach areas, ensuring all surfaces are free of contaminants. Once cleaned, the device should be immersed in a medical-grade disinfectant solution or sterilized using an autoclave, depending on the material of the airway device. Autoclaving is the preferred method for sterilizing reusable OPAs, as it uses high-pressure steam to eliminate bacteria, viruses, and spores. For single-use devices, proper disposal according to medical waste guidelines is necessary to prevent cross-contamination. Always follow the manufacturer’s instructions for cleaning and sterilization to maintain the device's integrity and ensure compliance with infection control standards.Storage and Handling of Oral Airway Kits

Proper storage and handling of oral airway kits are critical to maintaining their functionality and ensuring they are readily available during emergencies. Airway devices should be stored in a clean, dry environment, away from direct sunlight and extreme temperatures, as these conditions can cause degradation of the materials over time. Many healthcare facilities use designated storage cabinets or airway management kits to keep devices organized and protected from contamination. Each kit should include a range of airway sizes to accommodate patients of varying sizes, from infants to adults. Devices should be stored in their original packaging or sterile containers to prevent exposure to dust and pathogens. Additionally, it is essential to regularly inspect the storage area to ensure that all devices are within their expiration dates and that single-use items have not been opened prematurely. Proper labeling and organization of the kits can save valuable time during emergencies, enabling healthcare providers to select the appropriate device quickly.Recognizing Signs of Wear and Tear

Regular inspection of airway devices is essential to identify signs of wear and tear that could compromise their effectiveness or safety. Over time, repeated use and sterilization can cause materials to degrade, leading to cracks, discoloration, or loss of structural integrity. For example, an oropharyngeal airway with visible cracks or rough edges can cause trauma to the patient’s oral cavity during insertion. Key signs of wear and tear to look for include:- Cracks or Breaks: Inspect the device for any visible damage, such as cracks or fractures, which can render it unsafe for use.

- Discoloration: Fading or discoloration may indicate material degradation, which can compromise the device’s durability.

- Deformation: Check for warping or bending, as this can affect the fit and function of the device.

- Loose or Missing Components: For devices with multiple parts, ensure that all components are intact and securely attached.

Airway Emergencies and Management

Identifying Airway Emergencies

Airway emergencies are critical situations where the patient’s ability to breathe is compromised, requiring immediate intervention to restore oxygenation and ventilation. These emergencies can arise from a variety of causes, including trauma, medical conditions, or foreign body obstructions. Recognizing the signs of an airway emergency is the first step in providing effective care. Common indicators include difficulty breathing, stridor (a high-pitched wheezing sound), cyanosis (bluish discoloration of the skin), and visible signs of airway obstruction, such as choking or gasping. In trauma cases, airway emergencies may result from facial injuries, swelling, or bleeding that obstructs the airway. Medical conditions like anaphylaxis, epiglottitis, or severe asthma can also lead to airway compromise. Additionally, foreign objects lodged in the throat or trachea are a frequent cause of airway obstruction, particularly in children. Early identification of these emergencies is crucial, as delayed intervention can lead to hypoxia, brain damage, or death. Healthcare providers must be trained to quickly assess the situation, identify the underlying cause, and initiate appropriate management strategies.Use of Supraglottic Airway Devices

Supraglottic airway devices (SGAs) are essential tools in managing airway emergencies, particularly when endotracheal intubation is not immediately feasible. These devices are designed to sit above the vocal cords, providing a secure airway without the need for direct visualization of the trachea. SGAs are commonly used in prehospital settings, during anesthesia, and as a backup option in difficult airway scenarios.- Types of Supraglottic Airway Devices:

- Laryngeal Mask Airway (LMA): A flexible device that forms a seal around the laryngeal inlet, allowing for effective ventilation.

- I-Gel Airway: A gel-like, non-inflatable device that conforms to the patient’s anatomy, offering a quick and reliable airway solution.

- Combitube: A dual-lumen device that can be used for ventilation regardless of whether it is placed in the esophagus or trachea.

- Indications for Use: SGAs are ideal for patients who are unconscious and require airway support but do not have a gag reflex. They are particularly useful in cases of cardiac arrest, respiratory failure, or when intubation attempts have failed.

- Advantages:

- Easy and quick to insert, requiring minimal training.

- Effective in maintaining oxygenation and ventilation in emergency situations.

- Less invasive than endotracheal intubation, reducing the risk of trauma to the airway.

Strategies for Effective Airway Management

Effective airway management requires a systematic approach that prioritizes patient safety and ensures adequate oxygenation. The following strategies are essential for managing airway emergencies:- Initial Assessment and Preparation: Begin by assessing the patient’s airway, breathing, and circulation (ABC). Determine the level of obstruction and identify any immediate threats to the airway. Prepare all necessary equipment, including suction devices, airway adjuncts, and oxygen delivery systems, to ensure a rapid response.

- Positioning: Proper positioning is critical for maintaining a patent airway. Use the head-tilt, chin-lift maneuver to open the airway in patients without suspected spinal injuries. For trauma patients, the jaw-thrust maneuver is preferred to avoid exacerbating cervical spine injuries.

- Use of Airway Adjuncts: Airway adjuncts, such as oropharyngeal and nasopharyngeal airways, can help maintain patency in unconscious patients. These devices are particularly useful in preventing the tongue from obstructing the airway while preparing for more advanced interventions.

- Ventilation Support: If the patient is not breathing adequately, provide ventilation using a bag-valve mask (BVM) with supplemental oxygen. Ensure a proper seal and monitor for effective chest rise and fall. In cases of severe respiratory distress, consider advanced airway devices like SGAs or endotracheal tubes.

- Addressing the Underlying Cause: Effective management involves identifying and treating the root cause of the airway emergency. For example, perform the Heimlich maneuver or back blows for foreign body obstructions, administer epinephrine for anaphylaxis, or suction secretions in cases of excessive mucus or blood.

- Team Coordination: Airway emergencies often require a team-based approach. Clear communication and role delegation are essential to ensure that all aspects of care, from equipment preparation to patient monitoring, are addressed efficiently.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: What is an oropharyngeal airway (OPA)?

A: An oropharyngeal airway (OPA) is a medical device used to keep a patient’s airway open by preventing the tongue from blocking the oropharynx. It is inserted into the mouth and positioned in the oropharynx, making it particularly useful for unconscious patients or those with a diminished gag reflex to facilitate breathing.

Q: How do you properly insert an oropharyngeal airway?

A: To insert an OPA:

- Select the correct size by measuring from the corner of the mouth to the angle of the jaw.

- Open the patient’s mouth and, if needed, use a tongue depressor to move the tongue forward.

- Insert the airway with the curved side facing the roof of the mouth.

- Once the tip reaches the back of the throat, rotate the device 180 degrees so the curve follows the natural contour of the tongue.

- Gently push it into place, ensuring the flange rests against the lips or teeth.

Q: What are the indications for using an oropharyngeal airway?

A: The OPA is indicated for patients who are unconscious and lack a gag reflex. It is particularly effective in preventing upper airway obstruction caused by the tongue falling back against the epiglottis, which can block airflow. It is commonly used in emergencies, during anesthesia, or in resuscitation scenarios.

Q: What are the potential complications of using an oropharyngeal airway?

A: Potential complications include:

- Airway Trauma: Improper insertion can cause injury to the oral cavity or pharynx.

- Incorrect Sizing: A device that is too small may fail to maintain the airway, while one that is too large can cause obstruction or trauma.

- Gag Reflex Stimulation: Inserting an OPA in a conscious or semiconscious patient may trigger vomiting or aspiration. To minimize risks, always assess the patient’s condition and ensure proper sizing and placement.

Q: How does the Guedel airway relate to oropharyngeal airways?

A: The Guedel airway is a specific type of oropharyngeal airway with a distinctive design that includes a hollow center, allowing for suctioning or ventilation. It is widely used in clinical practice and is often referred to interchangeably with the term OPA. The Guedel airway’s shape ensures effective prevention of tongue-related airway obstruction.

Q: What is the difference between oropharyngeal and nasopharyngeal airways?

A: The primary difference lies in their placement:

- Oropharyngeal Airway (OPA): Inserted through the mouth into the oropharynx, suitable for unconscious patients without a gag reflex.

- Nasopharyngeal Airway (NPA): Inserted through the nose into the nasopharynx, ideal for patients with an intact gag reflex or when oral access is restricted. Both devices are used to relieve airway obstruction but are chosen based on the patient’s condition and clinical needs.

Q: How can you assess the position of an oropharyngeal airway?

A: To confirm proper placement of an OPA:

- Ensure the flange is resting against the lips or teeth without causing trauma.

- Observe for improved breathing and effective chest rise.

- Listen for clear breath sounds and check for the absence of airway obstruction. If the device is too small, too large, or incorrectly positioned, it may need to be adjusted or replaced.

Q: What role does the OPA play in airway management during anesthesia?

A: During anesthesia, the OPA is used to maintain an open airway by preventing the tongue and soft tissues from collapsing and obstructing airflow. It serves as an adjunct to other airway management techniques, such as endotracheal intubation or bag-valve-mask ventilation, ensuring adequate oxygenation and ventilation throughout the procedure.

Q: What is an airway emergency and how do OPAs help?

A: An airway emergency occurs when there is a risk of airway obstruction, which can lead to hypoxia, respiratory failure, or cardiac arrest. Oropharyngeal airways are critical in such situations as they help relieve upper airway obstruction caused by the tongue or soft tissues, ensuring that oxygen can flow freely to the lungs and preventing further complications.

Conclusion

The oropharyngeal airway is a vital device in airway management, providing a simple yet effective solution for maintaining airflow in critical situations. Proper sizing, insertion, and care are essential to its success, ensuring patient safety and optimal outcomes. As a cornerstone of emergency care, the OPA continues to save lives and improve respiratory support in diverse clinical scenarios.

Login with Google

Login with Google Login with Facebook

Login with Facebook