Let’s face it: children between the ages of one and three tend to be abrupt with some behaviors. It’s not unusual for infants or toddlers to find tiny objects in their surroundings and perfect them. The worst instance is swallowing these objects, which can be a painful experience for the child and, on some occasions, life-threatening. So, we have structured a plan or a step-by-step guide for young parents to assist their children during such an emergency. Now and then, children tend to choke whilst eating, so the first part of the article enlists the reasons why a toddler might choke and how a person can learn to recognize if a child’s airway is blocked. Then, the article further explains how to provide the infant or toddler with adequate first aid. It describes and illustrates how specific recommendations for children ages one to eight years can be performed according to most medical experts. All these techniques, such as back strikes and lower chest thrusts, are incorporated with more advanced medical treatments. This guide also underlines specific recommendations to lessen the chances of a prenatally distributed incursion. That said, this particular query strengthens a person's understanding of highly solitary congregated environments. By the end, if people follow these easy guides, the chances of a choking incident will inevitably significantly reduce. Besides, people can save a child’s life by applying the instructions forward and adhering to them effectively.

What are the signs that a two-year-old is choking?

A toddler, if two years old, could cough, cry, and speak but might sometimes display ill effects during coughing. Other symptoms may include having bluish skin because of lack of oxygen. Such children might also scratch their throat, which is a common sign of choking, or even wheeze or breathe without sound. If there is no immediate action taken during the choking, then the toddler might faint. A three-year-old would be able to talk more, which means more factors need to be considered.

Recognizing the Difference Between Choking and Coughing

According to my observation, while assessing toddlers, my main focus is on the amount and depth of cough produced by a two-year-old to determine whether the case is apneic or a cough. In most cases where the child can cough and is also able to inhale shows that the airway is not completely blocked but rather a part of it is hindered, this means the child can remove the suffocating foreign body from his neck by himself. However, the onset of weak coughs or even the inability to produce sound with symptoms like a hand on throat, whooping cough, blue skin (cyanosis), or silence indicates a complete airway blockage, which means immediate help is needed. This is important because a strong cough implies that the body is still trying to push the door, restricting airflow. A strong cough indicates the insult has been severe and would likely require back blows and/or abdominal thrusts to open the door.

Common Signs and Symptoms of Choking in Toddlers

Detecting choking in toddlers involves looking for some specific signs and indicators that should emerge. Essential features include breathing or speaking difficulties, weak coughs or lack of coughing accompanied by stridor, a high-pitched sound during inhalation, or even complete silence. Another essential feature is the presence of cyanosis, defined as an abnormal bluish coloration of the skin, lips, or nails. In distress situations, where a toddler is beginning to choke, he or she is also likely to grasp his or her throat and look panic-stricken, with bulging eyes and frantic movements.

If a complete obstruction of the airway caused the choking, asphyxia could set in very quickly, and oxygen levels in the body would drop to below 90%. Also, with Chest percussion and Back blows being ineffective, the toddler might practically be drooling as he or she cannot swallow anything. If a choking toddler is not supported quickly and intently, their brain could suffer irreparable damage in a span of 4 to 6 minutes due to hypoxia. This concern could also be addressed by monitoring transfusion in choking toddlers and adjusting the other changes in airway openings accordingly.

When to take immediate action

In a situation of a choking case, when I see a person with other signs of an obstructed airway too, like the inability to move, speak, or make sounds, alongside cyanosis and a threatening scan, then an oxygen saturation level of 90%, I do not hesitate to act. Another scenario that makes me act instantly is when the person in question is not able to respond or is showing physical signs of distress, e.g., holding onto their throat. Have you ever seen oxygen saturation falling to less than 90% or any visible symptoms of hypoxia, such as blueish discoloration of the skin and lips? First response measures include back blows followed by abdominal thrusts (also known as the Heimlich maneuver), chest compression, and active pursuit of emergency support.

What is the first step in helping a choking two-year-old?

When attempting to help a two-year-old who is choking, the first thing that should be done is to check the child’s condition. The aim is to ascertain how deep the obstruction is within the throat. If the child has some form of productive cough, they should be aided to cough more as this may help unclog the throat. In an incident where the child is unable to cough or there is a requirement to cry or breathe, then slap the child’s back in between the shoulder blades five times with the heel of your hand and then apply five chest thrusts. The child’s head should be lower than their chest during these moves.

Assessing the situation quickly

Usually, children who have trouble breathing or coughing insufficiently will require a lot of attention on my part. For the more able children, I prefer that they try to spam cough, only staying around them to assess whether I need to give further assistance. In cases if the children are mute, cyanotic or even have severe complete obstruction of airways, I rapidly proceed to position them in an upright setting, then place my hands on their upper back and, with much force and impact,t contact with their upper back five times and with the same position five more times contact their thorax during expiration, while ensuring that their head is even lower than their chest. I start with a dim and casual impression but the moment they have their airway blocked for a longer duration I am ready to change it all with CPR or a 911 call.

Calling for emergency help

Should the situation persist despite the use of procedures such as back blows and chest thrusts, I immediately request the parents to call the emergency number 911, tell them my location, and clearly describe the child. For instance, I tell the caller that I have already given back blows and lower chest thrusts and whether the child can talk or has lost consciousness. Technical parameters I consider include assessing for continued inability to breathe, talk or cry, looking for cyanosis, which is a bluish discoloration of the skin and monitoring loss of consciousness. If the child fails to respond before the help arrives, I prepare to perform CPR and cover the nose and mouth of the child, compress the chest fifteen times, and place two fingers on the head as directed by the American Heart Association. The last thing I tell them is that I stay where I am and do not hang up the phone while waiting for assistance from the authorities.

Positioning yourself to assist the child

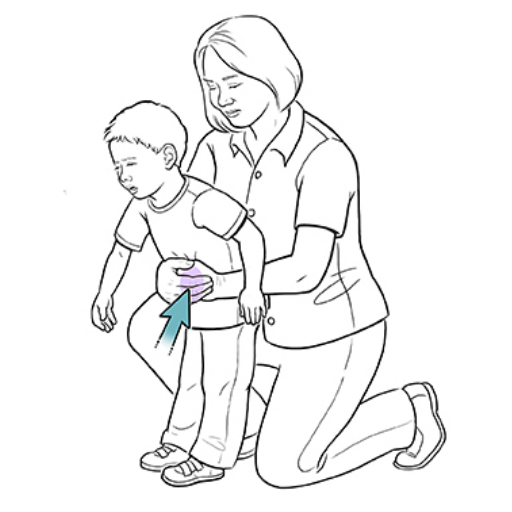

It is vital to ensure that the correct positioning has been achieved before assisting a choking child so that the relevant action is taken effectively and safely. First, I kneel to be the same height as the child and enjoy some stability and control during the procedure. When addressing an infant less than one year of age, definite support of the head and neck is provided, and the entire upper trunk is positioned so that it rests on my forehead, whereas the head faces slightly down with the face in my palm. But suppose the child is above one year. In that case, one of my legs slants slightly forward on the side, assuming a somewhat standing position while I am behind the child. The other hand is grasped around the child’s waist so that I can adjust the child’s position by leaning the child forward. Key technical parameters consist of maintaining the airways in a neutral position, applying back blows and thrusts with controlled force, and assessing the child’s behavior towards position changes. Stability, support, and posture are critical elements in this procedure as they help carry out the technique with minimal further risks to the child.

How do you perform back blows on a choking two-year-old?

To perform back blows on a choking two-year-old, first ensure the child is in a stable and supported position. Place the child in a forward-leaning posture, ideally positioned over your lap or supported by your arm, with their chest angled downwards. Use the heel of your hand to administer five firm back blows between the shoulder blades. Each blow should be controlled yet forceful enough to dislodge the obstruction. Continuously monitor the child’s response to each blow, and if the obstruction persists, proceed to chest thrusts while ensuring the airway remains in a neutral and open position. Always prioritize stability and ensure no excessive force is applied. Seek medical assistance if the foreign object is not expelled promptly.

Correct technique for delivering back blows.

To deliver back blows effectively on a choking two-year-old, adhere to the following steps and parameters to ensure safety and maximize the likelihood of success:

- Positioning: Place the child in a forward-leaning posture to leverage gravity. Support their chest with one hand to provide stability and ensure their head is lower than their torso.

- Alignment: Maintain proper airway alignment to prevent additional obstruction or injury. The head and neck should remain straight while leaning forward.

- Blow Delivery:

- Use the heel of your hand for precise impact.

- Target the area between the shoulder blades.

- Deliver up to five firm, distinct blows, ensuring each allows time to observe if the obstruction is dislodged.

- Force Control:

- Blows should be forceful enough to generate the necessary pressure but controlled to avoid potential injury to the child’s delicate structures.

- Avoid excessive force that could bruise or damage the child’s back or ribs.

- Monitoring:

- Continuously observe the child for changes in breathing, crying, or coughing, which may indicate clearance or further complications.

- If back blows are ineffective, be prepared to shift to another intervention, such as chest thrusts.

These parameters are based on evidence-based practice standards for managing pediatric airway obstruction and are critical for effective and safe technique delivery.

Number of Back Blows to Attempt

As per the present recommendations and guidelines, I would try performing five back blows at the maximum in the case of a child's airway obstruction. Each of the blows, in this case, should be hard enough to remove the obstruction possibly, but still, the child should be monitored after each blow to see how the child reacts. Such intervention would last as long as the back blows do, and such back blows, along with the force thrusts, would only be performed five times at the most. If the restriction were undone at that point, I would move on to the next step of the strategy, which is chest thrusts.

When to Switch to Abdominal Thrusts

I would switch to abdominal thrusts if the initial five back blows and subsequent chest thrusts fail to clear the obstruction and the child continues to show signs of severe airway blockage, such as the inability to cough, speak, or breathe. This step must be only taken if the child is over one year old, as abdominal thrusts are contraindicated in infants due to the risk of injury. The following technical parameters guide this decision:

- Age Consideration:

- Abdominal thrusts are appropriate only for children aged over one year.

- Signs of Airway Obstruction:

- Persistent inability to expel the obstruction after other maneuvers.

- Technique:

- Deliver each thrust by positioning behind the child, making a fist just above the navel, and pulling upward and inward forcefully yet controlled to create sufficient pressure to dislodge the obstruction.

These steps align with established pediatric resuscitation guidelines to ensure safe and effective intervention.

What is the proper way to perform abdominal thrusts on a toddler?

To properly perform abdominal thrusts on a toddler, follow these steps:

- Positioning:

- Stand or kneel behind the child, ensuring you are at an appropriate height for the maneuver.

- Place your arms around the child’s waist.

- Hand Placement:

- Make a fist with one hand and position it just above the navel, well below the ribcage.

- Grasp your fist with your other hand for support.

- Thrust Execution:

- Deliver quick, upward, and inward thrusts in a controlled manner.

- Repeat the thrusts as necessary, up to five times, or until the obstruction is expelled and the child starts breathing or coughing.

- Special Considerations:

- Avoid excessive force to minimize the risk of internal injury.

- Cease the procedure immediately if the child becomes unresponsive and begin CPR if trained to do so.

Always ensure these actions comply with pediatric first aid guidelines and seek emergency medical assistance immediately.

Positioning for abdominal thrusts on a small child

When performing abdominal thrusts on a more minor child, I will either be standing or kneeling, depending on his or her size. However, when I perform the maneuver, I want to be in the right position, so I maneuver so that my arms go around the child's waist while bringing the arms above the navel. I also want to make sure that my hands are in the right position to carry out the procedure without jeopardizing the safety of the child.

Correct hand placement and thrust technique

I would commence by making a fist with one hand, which I would then position just above the child’s navel but below the ribcage with one hand, whilst my other hand circles my fist. With that done, allowing the rib cage to compress with sufficient upward pressure, I would deliver the sharp thrusts needed to loosen the obstruction. I would be careful as to how much pressure I applied with my thrusts to ensure that I wouldn’t injure the child and that I conformed to children’s first aid guidelines while also making sure to keep a close watch on the affected child during the entire process.

Alternating between back blows and abdominal thrusts

As I turn between administering back blows and abdominal thrusts, I have a pattern to follow, which enables me to unblock the obstruction without risks. I start by giving up to five back blows with the heel of my hand against the child’s back between the shoulder blades, and these back blows are targeted, firm, and directed such that the child’s position will help remove the object. Should the airway obstruction still be there, I carry out five abdominal thrusts, as this will increase the force the diaphragm can generate. I continue the sequence of abdominal thrusts and back blows until the obstruction is removed or until the child becomes unconscious. Among the technical parameters are applying mild back blows to avoid causing trauma, having the child lean forward so that gravity will help in removing the airway obstruction, and ensuring the correct hand placement for abdominal thrusts, which are on the abdomen and just below the ribcage. These practices are in line with the strong recommendations of pediatric first aid.

What should you do if the child becomes unresponsive?

Make sure to contact the activities in case they could not reach before if the child does not react. In such situations, CPR should be initiated as a matter of urgency. Place the child onto a flat surface and start administering chest compressions at a rate of between 100 and 120 per minute until about one-third of the child’s chest is depressed. Determine Whether the airway is clear. If yes, proceed to perform mouth-to-mouth ventilation. Two inflations should be enough. Perform the cycle again, where you have 30 chest compressions followed by 2 mouth-to-mouth ventilation until help arrives or the child regains consciousness. All these procedures follow the routing procedure for pediatric care.

Starting CPR Immediately

If CPR is required, take the following steps promptly and adhere to the recommended technical parameters:

- Positioning the Child

- Place the child on a firm, flat surface to ensure effective compressions. Ensure their head is positioned to maintain a neutral airway alignment.

- Chest Compressions

- Compress the chest at a rate of 100–120 compressions per minute.

- Use the heel of one hand for infants or both hands (one on the other) for older children.

- Compress the chest to about one-third of its depth (approximately 4 cm for infants and about 5 cm for children).

- Allow full chest recoil after each compression to enable proper blood flow.

- Rescue Breaths

- Following 30 compressions, deliver two rescue breaths.

- Open the airway using the head-tilt, chin-lift technique.

- Ensure a proper seal over the child's mouth and nose (for infants) or just the mouth (for older children).

- Deliver a breath lasting about 1 second, observing for visible chest rise. Avoid overinflation.

- Continue CPR Cycles

- Repeat cycles of 30 compressions followed by two rescue breaths.

- Assess the child periodically for signs of recovery, but do not stop CPR unless directed by medical personnel, the child regains consciousness, or you are physically unable to continue.

These technical guidelines are based on pediatric advanced life support protocols to maximize the likelihood of resuscitation. Always prioritize calling emergency services to ensure professional medical assistance.

Checking for visible obstructions in the airway

To begin with, an examination of the mouth and throat should be performed for any foreign body, edema, or abnormality that may restrict airflow. Such an approach is critical in establishing whether there are any mechanical airway obstructions during the examination. Key signs to look for include food, vomitus, or small articles such as toys that may have been swallowed; swollen epiglottis or inflammation of the epiglottis, along with visible obstruction of passageways.

If one cannot directly see any obstructions but thinks the person may have an obstruction, then allowance can be made to see how air is coming through. This can be achieved by tilting the head backward while moving the chin upwards. Thus, the airway gets opened, known as the head-tilt, chin-lift method. If you think the person may have trauma, then do not attempt to do this, as it may only aggravate spinal injuries. A jaw-thrust maneuver should be done instead.

Among the key technical parameters is to guarantee that the minimum diameter of the open airway is at least 6–8 mm for adults, which enables proper ventilation. Apart from a breathing rate of approximately 12 – 20 for adults, observe chest expansion and whether adequate airflow is in constant flow. If the obstruction still is not reduced, other suction or Heimlich maneuvers can be implemented suitably, depending on the degree and the kind of blockage. A key focus should always be a clear airway to prevent a state of hypoxia or respiratory problems.

Continuing first aid until help arrives

In first aid, I always stay calm and concentrate on the injured person while waiting for the waiting for the paramedics. First, I check if the area is secure, and after that, I approach the person and evaluate him/her to see whether he/she can speak, is breathing, or perhaps has an injury that is bleeding heavily. Then, I stand ready to provide CPR or administer a defibrillator machine if one is there. To stop the gore, I keep steady pressure with either a clean piece of cloth or a bandage and dressing. I place the individual in as comfortable position as possible while observing them, centering on them, and stopping them from eating or drinking. While doing all this, I continue to reassure the patient while providing critical information to the emergency responders as soon as they arrive.

References

Choking Respiratory tract CoughFrequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: What are the signs of choking in a two-year-old child?

A: Signs of choking in a two-year-old child include difficulty breathing, coughing weakly or not at all, making high-pitched noises while trying to breathe, inability to cry or speak blue or gray skin color, and loss of consciousness. It's crucial to recognize these signs quickly to provide immediate first aid.Q: How do I perform the Heimlich maneuver on a choking two-year-old?

A: For a choking two-year-old, first give five back blows between the shoulder blades. If this doesn't dislodge the object, proceed with five abdominal thrusts (similar to the Heimlich maneuver). Stand or kneel behind the child, wrap your arms around their waist, and place a fist above their navel. Give quick, upward thrusts to try to dislodge the object.Q: When should I call emergency services if my child is choking?

A: Call emergency services (911 in the US or 999 in the UK) immediately if the child becomes unconscious, stops breathing, or if you cannot remove the obstruction after performing first aid. Even if you manage to dislodge the object, seeking medical attention is advisable to ensure no complications.Q: Are chest thrusts recommended for a choking two-year-old?

A: Chest thrusts are generally recommended for infants under 1 year old. For a two-year-old child, abdominal thrusts (similar to the Heimlich maneuver) are more appropriate. However, if abdominal thrusts are ineffective, chest thrusts can be used as an alternative method to dislodge the object.Q: What should I do if my two-year-old becomes unconscious while choking?

A: If the child becomes unconscious, lay them on a flat surface and begin CPR immediately. Start with 30 chest compressions followed by two rescue breaths. Before giving rescue breaths, check the mouth for any visible obstructions and remove them if possible. Continue CPR until emergency services arrive or the child starts breathing normally.Q: Do organizations like the Red Cross recommend any first aid apps for choking emergencies?

A: The American Red Cross offers a First Aid app that provides step-by-step instructions for various emergencies, including choking. This app is available for iOS and Android devices and can be a valuable resource for parents and caregivers. It includes information on choking in children and other first-aid advice.Q: What are common choking hazards for two-year-old children?

A: Common choking hazards for two-year-olds include small objects like coins, buttons, and small toy parts; round foods such as grapes, cherry tomatoes, and hot dogs; hard candies; nuts and seeds; large chunks of meat or cheese; and sticky foods like peanut butter. It's essential to be aware of these risks and take preventive measures to reduce the chances of choking.Q: How can I prevent choking incidents in my two-year-old child?

A: To prevent choking, always supervise meal times, cut food into small pieces (no larger than 1/2 inch), avoid high-risk foods like whole grapes or hot dogs, teach your child to chew food thoroughly, discourage eating while running or playing, keep small objects out of reach, and regularly check toys for loose or small parts that could cause choking.

Login with Google

Login with Google Login with Facebook

Login with Facebook